Is Global Crisis Care for Mental and Behavioral Health Possible?

I'm a suicide survivor who attended the Crisis Now Summit in Amsterdam this June. Here was my experience.

Content warning: This post has mention of suicide. If you are feeling tender, please know you can return to this piece at anytime. If you are experiencing suicidal thoughts or feel you could use immediate support and are located in the United States, please text or call 988. You are not alone.

New York in February is Frigid.

For several months of the year, everything in Manhattan dies. Trees curl up and harden. Grass browns or suffocates under heavy mounds of snow. Frozen water covers the streets and for months, we allow nature to go away for a little while. We let her fade and darken. Disappear, and appear lifeless.

I wanted, as a 19-year-old college student, to freeze over with the winter.

How am I supposed to keep myself so green and blooming in such a dreadful cold? How will I grow and keep my leaves open when conditions are so harsh? How, oh how, will I do this year after year?

There were few places to ask these questions when I was in college—fewer answers. I wanted to know how to cope with crippling insecurity without appearing incompetent. How to manage all the sadness and fear in my head without falling apart. How to kill the voice in my head that told me I was worthless without killing all of me.

How do I end just some of the lives inside of me?

Without an outlet for my thoughts, I retreated inward.

In the winter of 2008, I faded and darkened in the corners of my mind. I thought if I became lifeless, I might be able to escape the cold and wake up when the snow melted.

Instead, I woke up in a hospital wheelchair, tucked in the corner of a hallway on the psychiatric floor of the Queens Medical Center. I didn’t know where I was. For hours, I sat in that wheelchair, alone. I had not escaped the frigid cold, I’d entered it.

In ways, I thought I deserved to be abandoned in a hospital hallway. That my disregard for human life should leave me disregarded. That I was, as I suspected, sub-human, and this was the confirmation.

The reality is that I was a college student in a mental health crisis, and I was not equipped with the language, emotional safety, or awareness to seek care. And even if I had been equipped, compassionate, comprehensive, quality care did not yet exist.

When someone is in a mental health crisis, they need to feel safe to ask for help and have places that are actually safe to go.

When the cold front comes, we need places to warm our insides. When everything starts to harden and freeze over and the best solution feels like letting it happen, we need a place to go that reminds us leaves grow again.

Sixteen years have passed since that cold winter. And in those years, people have started to build safe places for the darkening minds. From text lines to fully equipped crisis care centers, there is a global effort to offer immediate and compassionate support to those in a mental health crisis.

Luckily, I am still here to witness these changes. As a result of sharing my story, I’ve had the privilege of learning from and collaborating with organizations in support of creating quality, comprehensive crisis care for all. And this June, I had a front-row seat to the undertaking.

This June, I flew to Amsterdam to attend the third global “Crisis Now” summit.

The summit was a global gathering of healthcare leaders, educators, government officials, first responders, people with lived experience, and others with the sole mission of improving crisis care. Specifically, how to create more cohesive, compassionate, and collaborative options that aren’t solely reliant on law enforcement or hospital emergency rooms.

“Like a physical health crisis, a mental health crisis can be devastating for individuals, families and communities. Too often, that experience is met with delay, detainment and even denial of service that can all add to a person’s trauma history” (“Crisis Now 2: Taking the Lead,” 2019).

We cannot plan for winter months of the mind. But hopefully, we can develop services that are designed to warm and tend to the cold of crisis without making it worse.

For two days we sat in conference learning, listening, and laboring. How are other countries providing mental health crisis care? What barriers exist? What constitutes “quality” care? And most importantly, what do people who have been in crisis have to say?

“I felt like I was being punished,” Soi Kraay reflected on her hospitalization after a mental health crisis. “And that was a feeling I already knew.”

Folks who have been through a mental or behavioral health crisis shared their stories at the start and end of each day. Their stories served as reminders that we are building systems for people—living, breathing, feeling humans. While saving money, streamlining systems, and operational management matters, none of it matters if it’s not helping the people who need the care, and how they need it.

“While a crisis cannot be planned, we can plan how we organize services to meet the needs of those individuals who experience a mental health crisis. It can also lead to hope, recovery and action.”

(“Crisis Now 2: Taking the Lead,” 2019)

Between peer stories, professionals from varying countries shared their experiences in providing crisis care.

In one panel featuring various first responders, Sean Russell, Chief Operating Officer and European Lead at the Global Leadership Exchange, shared that during his policing service career in the UK, he only used his baton a handful of times. In all other scenarios, he de-escalated situations with conversation and connection.

“The most powerful tool for de-escalation is not a weapon, it’s connection.”

-Sean Russell

Pierluigi Mancini, global thought leader on immigrant health and human disparities, reminded us that culture and language influence how we feel, express, and cope with crisis.

“Linguistic barriers exist at three levels, the literal meaning of the spoken word, the cultural meaning of the situation, and the context in which it is being used,” he said.

Without understanding cultural differences, professionals inappropriately diagnose and even admit people who might be expressing grief or emotions in response to a painful event. For example, while the term “ataque de nervios” might directly translate to “panic attack,” the cultural translation is missing: Often, an ataque de nervios is related to interpersonal stressors like grief or trauma.

Genuine curiosity and concern fueled the drive for efficient systems and action plans.

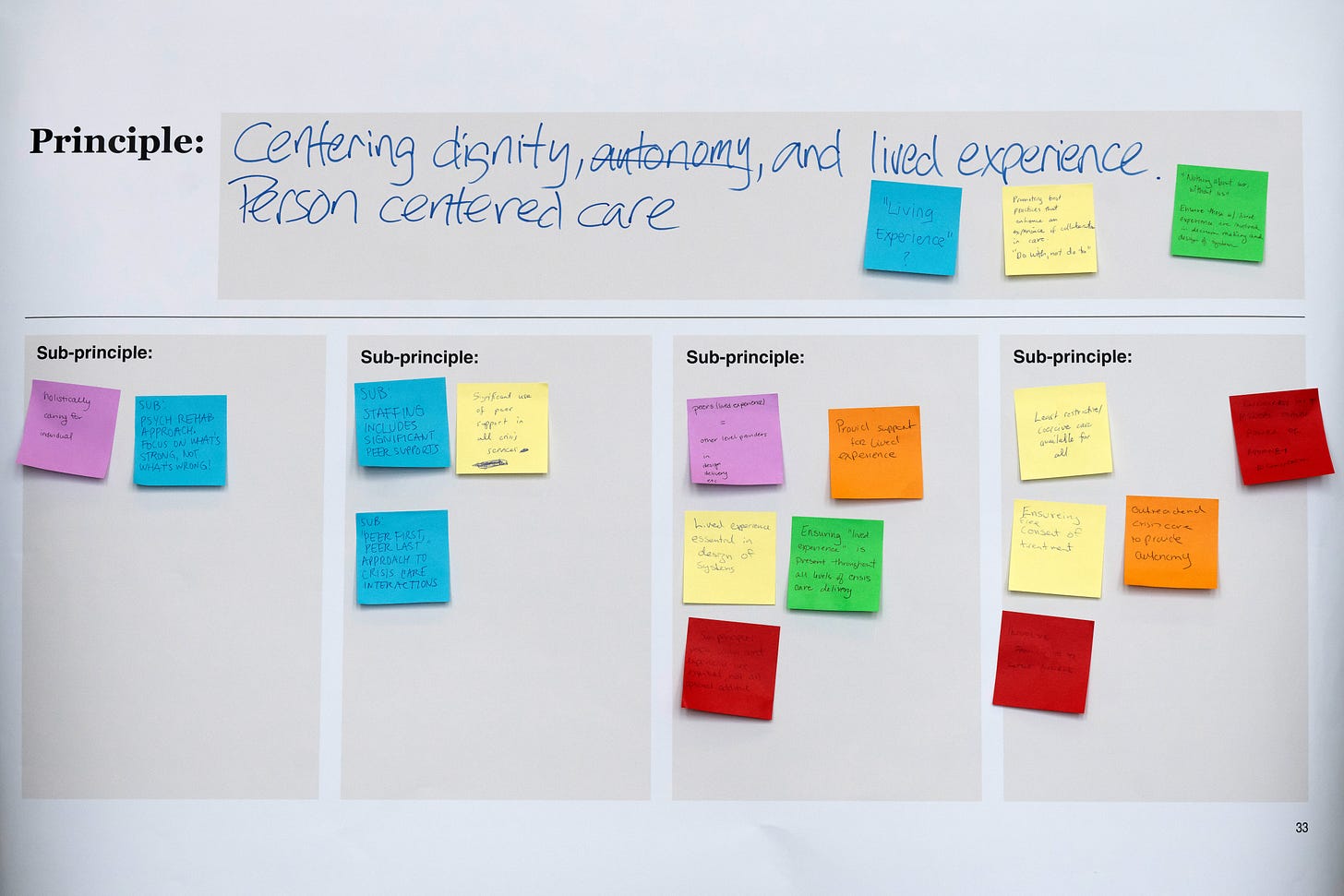

While one of the goals during the summit was to define global principles for crisis care and initiate concrete change, participants approached the process as a delicate investigation that required hard questions, sometimes with no answers.

One Australian attendee expressed their concerns for cultural sensitivity around creating global principles for crisis care: “How do we create global principles for a crisis care initiative if not all countries have representatives here to speak for their people?”

“A mental health crisis is not planned. It cannot be scheduled. It can happen to anyone... anywhere… anytime” (“Crisis Now 2: Taking the Lead,” 2019).

Crisis is universal: it can happen anywhere, to anyone, anytime. And, crisis is individual: each person has a unique expression of crisis and needs different kinds of support.

So how do we create global principles that honor diverse populations, resources, and expressions of crisis?

After a day of battling these questions, I escaped outside to catch my breath.

I found a park bench and stared into the Amsterdam air. I sat alone and tried to let the warmth of the sun soften me. I thought about how I felt sitting alone in that hospital wheelchair sixteen years ago. How nobody came to tell me what was happening or see how I was. How I had felt like a worthless person before entering the hospital, but sitting in that chair, I hadn’t felt like a person at all.

When I returned to the venue for dinner, wondering how so many moving parts might ever merge together, I heard a voice to my left.

“It’s so hard, isn’t it. I’m glad you’re here, though. How are you doing?”

I tilted my head towards the voice and met the woman’s gaze. My lips curled upwards into a small smile, mirroring hers.

“I’m very overwhelmed, incredibly inspired, and just grateful to have lived long enough to be here.”

“Don’t forget, the sun is above you, the ground below you,” she beamed.

I thanked her and remembered that none of this matters without eachother. That any system of crisis care is not care without connection. That we might not build the bones of the structure perfectly, but we can try to give it a heart.

Anytime I felt myself getting cold during the rest of the summit, I looked at her.

When panelists debated the presence of folks with lived experience as peers in crisis care, and I felt a pang of being “other” or “broken” because of my own lived experience, I looked at her. When first responders reminded us that crisis doesn’t just impact the person in crisis, and that comprehensive crisis care must include the family and networks of the person involved to reduce trauma, I looked at her. When Dr. Ravivarma Rao Panirselvam reminded us that all people truly want is to be seen, I looked at her.

The sun is above me, the ground below me.

At the end of the two days, I felt hopeful. Not that we would get anything perfect or right, but that we were trying. That despite what I believed sixteen years ago, people do care, and people are listening.

I know now that in winter seasons of the mind it’s ok to ask for help.

And though the voice that calls me a burden still cries out, I can quiet it. I can look up and out and find a person who meets my cold with compassion, and feel the warmth.

Changes to how we understand and care for eachother didn’t happen because we all sat alone in the corners of our mind.

Change happened because we gathered in rooms like this and asked answerless questions. Change happened because people with lived experience walked out of hallways and shared their stories.

Change happened because of a determination to see humans as humans, treat people as people, and with as much tenderness and warmth as possible, provide safe places for them to step out of the cold.

To learn more about the Crisis Now Summit in Amsterdam and follow the updates from the event, go to www.crisisnow.com or subscribe for emails from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors below.

Rachel Havekost is a writer and mental health advocate. She has been sharing her experiences with mental illness, grief, and being a human in hopes of helping others feel less alone. Read more of her story in her memoir, “Where the River Flows,” and consider subscribing to her Substack to support her writing.

Learn More about Crisis Now and its partners

“Crisis Now is led by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) and developed with the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, and RI International.”

Read the 2019 International Declaration from the 2019 Crisis Now Summit here.

Partners of the Crisis Now Summit

LEAD ORGANIZATION

NASMHPD:

National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors

SUPPORTING ORGANIZATIONS

National Alliance on Mental Illness

FOUNDING PARTNERS

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention

988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

National Council for Mental Wellbeing